Second Gen Students Reflect on Experiences

By Faith Zhao

Classmates provide insight into culturally diverse identities

In 1999, Shucayb Harir ‘26‘s parents immigrated to the U.S. to escape war in Somalia. They started off in the lower class and slowly worked their way up, battling through the tough trials as an immigrant in the U.S.

Jay Ali ‘26 brings his parents’ story to the table, saying “It was a hard process, I know that. Documentation…and housing, find[ing] somewhere to live.” Racism was very prevalent in his parents’ lives, explaining that “[my dad] took some big position at some power plant and every time he went there to work, there would always be cops looking for anybody that wasn’t the same skin color as your average citizen living in America. My dad got stopped eight or nine times in two years and another one of his co-workers got stopped like 21, 22 times.”

Coming to America can be seen as the greatest form of love and care for a family: “They just wanted a better life for me in America and like for me to be able to study here and honestly, at least in their community, the best thing that you can do is to leave India,” explains Krisha Pillai ‘26. “A lot of people end up going to college internationally and the best thing you can do for yourself is to leave, that's the smartest thing you can do.”

The Indian education system is the reason why people want to leave; one chance at one score on the entrance exam determines the trajectory of someone’s entire life.

Pillai’s parents came to America just to give birth to her: “My parents are definitely like we came here just to have you and like for you to have a better education so like ‘you better do stuff.’ Especially since I came to Blake late, they’re like we’re spending all this money for you to go to a private school.” The pressure from parents to do well is often corroborated with a comparison between a parent’s life in their home country to a child’s in America. “Like she always brings up how she was independent at like fifteen and she went to college at that time and she was all by herself at like fourteen, fifteen” Pillai said. Familial pressure incessantly knocks, sometimes bangs, at the back of students’ minds.

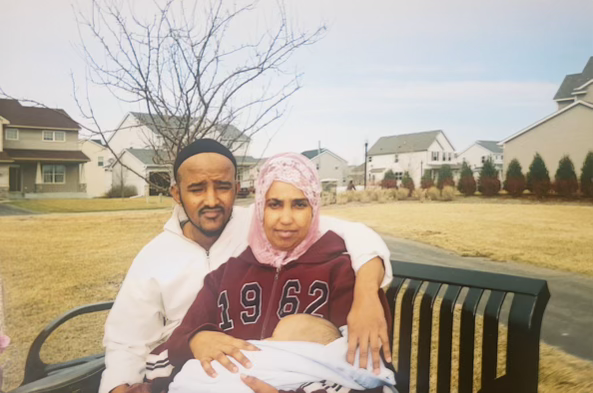

Pillai with her parents in Chicago in the year 2008.

Pillai with her parents in Chicago in the year 2008.

At last year’s conferences, Harir and his family sat down to meet his English teacher. Anna Reid praised Harir on his memoir project, saying “Oh, his poetry is so good!”

Away from teachers, when he left conferences, his parents yelled, ‘What is this school trying to do, trying to make you a poet or something?! That's not what I wanted for you, why do you like English?’”

“My parents, as much as I love them, they threaten me like if [I] don’t become this [they’ll say] ‘I’m not going to be proud of you’...it can be hard sometimes,” said Harir.

The background and experiences that immigrant parents go through are drastically different from their own experiences in America. The woven basket of the stories between a child and a parent will often have wide gaps that students have to fill.

Ali helps his mom, “[There is] stuff like helping my mom understand things that are foreign. Even now like group events like Blake and stuff [like] the Steiner thing–my mom was so confused.”

“Even today my parents still don’t understand the interims when they come out. They still think that they're supposed to be great, and then when there's nothing, they like getting mad at me, saying, ‘You're trying to hide your grades?” Harir jokingly laughs. “Like they’re more used to the traditional system, you get As Bs, and Cs, but there are just certain classes where teachers might take longer to put out grades. I don't know how to describe it, [but] they’re not really used to this different system.”

Parents’ cultures differ not only in societal systems but also in mindsets. Michelle Elliott ‘25, whose parents immigrated from Liberia to America to escape war, describes some of her family discussions; they’re like parallel lines, ideas sometimes don’t touch.

“If [my dad and I] have disagreements sometimes I feel like I can’t necessarily have a conversation about it cause this is the way it is by the book. And I understand that maybe because when he was going through war and trying to get out like if his mom said there [was] no food, there was no food. I feel like it helps me understand [them] in that way.”

Knowing that the viewpoint of a parent is “like a whole other world” as Ali puts it, understanding family stories of building a new life in America allows for an intersection between the two parallel lines of ideas.

Although there is a building connection between self and parent, there can be a divide between the “American” world and one’s own family. “When I was younger I was embarrassed, Ali continued, [There] were these parents who were fluent and my mom and dad were from like another world.”

Ali’s parents fled from Somalia to Sweden in the early ‘90s where his brother Bile Ali was born. In the early 2000s his family moved to Minnesota where they encountered adversities as Ali illustrates, “[There is] stuff like helping my mom understand things that are foreign.”

Ali’s parents fled from Somalia to Sweden in the early ‘90s where his brother Bile Ali was born. In the early 2000s his family moved to Minnesota where they encountered adversities as Ali illustrates, “[There is] stuff like helping my mom understand things that are foreign.”

In the sea of white American Blake parents, Harir immediately sees a contrast. His mother. “When I first came to Blake I felt like there was a divide…it was kind of superficial of me to think that but I was kind of embarrassed because my mom wears a niqab. She really sticks out…At first, I was not really proud of it and even today I’m not really sure if I’m proud of it.”

All of these interweaving and complicated experiences are integral components of a bigger growing story. “I feel like everything that they went through and what they are still going through as an immigrant in America today is so important and a part of this American identity cause we’re [all] a part of this thread. Harir comments, “We’re all a part of America.”

The story unfolds and lines touch. “I kind of realized this place was a sanctuary of peace because for the part of the time they were alive, they were involved in the war and [they saw] their family members die. I can see why they like America so much. I’m starting to realize why I like America too,” Harris notes.

“It can be annoying sometimes but it's fine I can do it.” JayJay Deng ‘28 explains how he has to translate his parents’ text messages.

“Knowing how hard and knowing the struggle and journey to get here just for a better life, like I know I have to perform and meet their expectations because they didn’t come here for nothing right? It adds pressure but that’s just life man.” Ali articulates his drive to do better.

“Growing up with parents who don’t understand the culture as much as other people who do and having to navigate being that third party,” Ali says “yea it's not that bad.”

“I would still wish that it happened because it's such a part of my identity.” Harir doesn’t want to erase the negative experiences. “It's just there it's a part of me.”